The dream and goal of my life was to write a novel. I had made a precarious living as a writer from age twenty-three until 1968 when I was thirty-six years old but I still hadn’t written the novel. I topped off my journalistic career by writing what became the entire issue of The Atlantic (March, 1968) called “Supernation at Peace and War,” the result of traveling throughout the country to report on the effect of the Vietnam war on America. That was published as a book, so I had a little money ahead of the game, and out of the blue I got an unexpected grant in writing from The Rockefeller Foundation. For the first time in my life I had a year free to write. This was it. Now or never. If I couldn’t write the novel now, I knew it would never happen.

I had lived in New York and Boston all my adult life, and I wanted to go someplace new. Friends in Los Angeles found me an apartment on Ocean Front Walk in Venice, California, which in those days was a run-down haven for hippies. The canals were dry, most of the buildings – except for those facing the ocean –were going to seed. I set up my portable Olivetti on a dining room table with a plate-glass view of The Pacific. I sat for days that became weeks and I began to see a story of two friends – seemingly opposite types, the jock and the nerd – both getting home from the Army during the Korean war; getting home on the same train and spending the summer trying to figure out what to do with their lives; questioning everything. I tried to set the novel in Cleveland (that wouldn’t get me in trouble) but I quickly realized that was impossible, since I knew nothing about Cleveland. These guys were coming home, and the only home I knew was Indianapolis. I hadn’t lived here since graduating from Columbia, but I knew its streets, its language, and I knew the era I wanted set the story in – the nineteen fifties. I honed in on the summer of ’54.

This was my basic rule: tell the truth – the only truth we have, which is what we know – in our heart, in our gut. This was my rule: don’t write what people are supposed to feel, write what they really feel; don’t make them talk the way they’re supposed to talk, write the way they really talk; don’t write the way people are supposed to behave, write the way they really behave. I let the story lead me.

I worked about a month to get the first sentence. It had to be right. It was like getting the first note of a song, the pitch had to be right or the rest wouldn’t be in tune. Then the first paragraph and then in another month I was getting whole pages. A page, maybe two a day. I followed the characters. All I knew was that they got home in May and they would leave the city in September and go to New York. I remembered a part of a poem by Carl Sandburg that moved me in high school. The poem was called “The Red Son.” These were the lines I remembered:

“. . .There is no pity of it and no blame/ none of us is in the wrong/ after all it is only this/ you for the little hills and I go away.” I got up to writing two or three pages a day and I would walk out to the Venice pier at night. Sometimes friends came over on weekends and I made White Russians in a blender and we drank. There were demons in me that feared my writing. After about six months I crashed a car, all alone, and walked away. No injuries, but the car was totaled. I went back to Boston where I felt safe.

I had an office at The Atlantic and went there every day when the other people did, showing up at 9 o’clock and working till lunch and taking a break with the others, then going back to work. Now I was getting four or five or six pages a day. It started to flow. It was like taking dictation. Most of the others left the office at 5 but I stayed writing until Joe Internacola started turning out the lights and closed the place up and he and I would go out for pizza and a beer and I would go home and sleep and get up the next day and go to work.

When I finished, the publisher who was considering the book told me he was sending it to Kurt Vonnegut to ask his opinion. I had no idea what to expect. I had met Vonnegut once in my life, at a dinner in Cambridge six years before; we had corresponded in a friendly way, but I had no idea what he’d think of my novel. The publisher called me some days later and read me a telegram he’d just got from Vonnegut: “You must publish this important book. Get this boy in our stable.” Kurt was like The Godfather of the book. He came to Boston and we had lunch at Jake Wirth’s, a German restaurant with sawdust on the floor. On publication day his wife Jane, who exuded warmth and light, came with him to Boston and we had dinner with Sam Lawrence, the publisher who Kurt said, “saved me from smithereens.” Me too, although I much later went back to smithereens. We all had dinner and I had a date with an admiral’s daughter.

Kurt reviewed the book in Life magazine. He said, “Having written this book, Dan Wakefield will never be able to go back to Indianapolis. He will have to watch the 500 mile race on television.” When the book came out, I heard that two or three men from Indianapolis were going to come to Boston and beat the crap out of me. One man was going to come to Boston and shoot me. One man called to tell me he was going to come to Boston and shoot me. His son called and said “You should take him seriously – he has a gun and he shot his third wife in the leg.” The book was taken by the Literary Guild and it turned up on the Time magazine bestseller list. It was in a mass market paperback edition for a long time. It has always been in print since 1970.

It came out the summer that my Shortridge Class of ’50 had its twentieth reunion. I didn’t go. I asked if they talked about it. I was told that the main speaker was Dick Lugar and someone asked him if he had read the novel. He said, “I received it in a plain brown wrapper.” That made me laugh. Because Lugar had done great things for the city and for the world, a lot of people didn’t understand he had a great sense of humor.

I didn’t come back until the Central Library invited me to come and speak in 1987 and asked me to write a piece for their newsletter before I came. I said, “I come in peace.” I saw some old friends from Shortridge and that was very nice and a lot of fun. Someone published a later edition of the book and my friend Sara Davidson, author of the classic Loose Change: Three Women of the Sixties, wrote a perceptive new introduction.

Five different movie companies optioned the book and tried to make a movie of it but it never worked. They wanted to set it in L.A. or Toronto. One of them wanted to “update it” to the ‘80s but that would have made no sense. It was about the attitudes and ambience of 1954. I quoted stories from magazines and newspapers of that year in the novel.

Out of the blue two young guys, a producer and director, came to me in ’95 and wanted to make a movie and have me write the script and set it in Indianapolis. No one had thought of that before. We did it in ‘97, with help from a lot of people here brought to us by the late Jane Rulon, the marvelous heart and soul of The Indiana Film Commission (abolished the next year by the new governor.) We worked like people possessed by a dream. We were blessed by a great cast of Ben Affleck, Rose McGowan, Jeremy Davies, Rachel Weisz, who were all unknown at the time. Six months later Ben Affleck was in “Good Will Hunting” and everyone became famous. Jill Clayburgh and Leslie Ann Warren played the mothers and they were already famous. A great guy named John Gallman, who reinvigorated the Indiana University Press, republished the book in an edition that used the poster of the movie for the cover, which is standard practice for books that are made as movies.

I wrote the script of the movie but it didn’t do well in the marketplace. It was one thing to read about painful things in a book but another thing to see them brilliantly acted out in a movie. The movie made a lot of people uncomfortable, including many reviewers, except for Roger Ebert, bless his soul. He said the movie was more true to his own time of growing up than any other movie he knew. His then partner Mr. Siskel turned thumbs down because he said he liked “American Graffiti” better.

So it goes.

The young guys in the movie and the book in 1954 do fantasize about women in bikinis and look at the pinup girls in Playboy, like millions of other young men of their time did and some still do although they are not supposed to. Those pictures in magazines have become like ancient cave paintings compared to what is dramatized in millions of ways on the internet, television, social media and all the innumerable forms of communication of murder and hate and life-killing kinds of sex and denigrations of the human body that are blasted at us every night and day.

Some women (men too!) hated the book and the movie and some have thanked me for it – sometimes for unexpected reasons. A few years ago I went to speak to the Butler class of Susan Neville, one of the true friends I have here (and in my whole life), and an older woman student in the class – maybe in her forties – came up to me and said she wanted to thank me for writing the novel. She said she gave her daughter a copy when she turned sixteen.

No one had ever told me that before.

“Why did you do that?” I asked her.

“Because,” the woman said, “I told my daughter that while those boys take you out and whisper romantic stuff, this is what they’re really thinking.”

Most of the women who have appreciated the book and the movie have told me they appreciated a man telling how men are sometimes vulnerable and fearful of sex and sometimes fail to perform and it is painful for the man as well as the woman. It is taboo for men to admit to such things for fear it means they are not a man, having failed to perform in the action that supposedly defines a man.

Some men didn’t like this to be revealed, but some appreciated this secret, this fear, this human failure admitted and brought into the open. Kurt Vonnegut must have appreciated that when he wrote as a blurb for the paperback edition of the book that Going All The Way was “the truest and funniest sex novel any American will ever write.” Of course it is not a “sex novel” by any customary definition, but a novel that dramatizes honestly some of the perplexities of young people dealing with sexual issues. In all its editions – Book Clubs, paperbacks, reprints – , the novel has sold a million copies. So it must have struck a nerve or seemed “true” to a lot of people.

I wouldn’t change a word of the book. If I could write the movie script again I would eliminate a lot of the talk at the end of the movie, trying to “explain” things that can’t really be explained. That’s all.

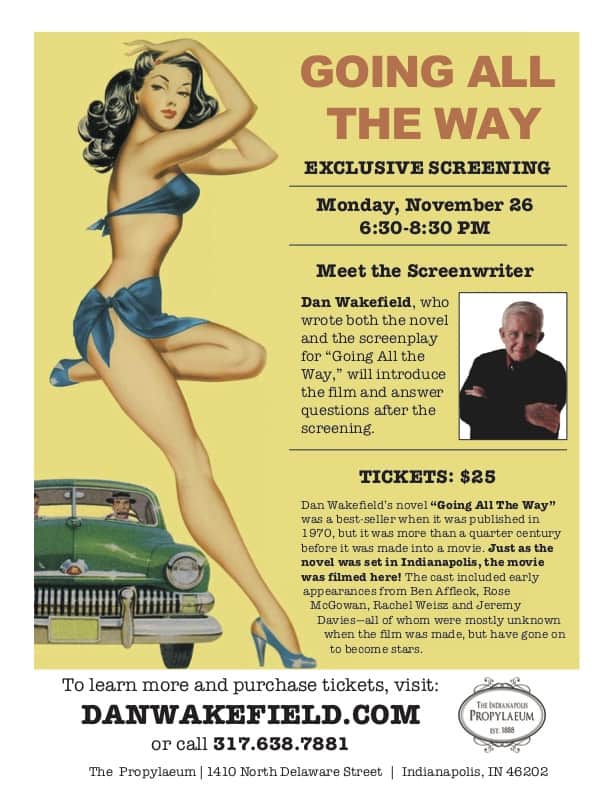

Without thinking, I used the movie poster on a flyer promoting the screening of the movie on Monday, November 26, at The Propylaeum, where I will introduce the movie and answer questions afterwards. After the flyer was flying around, I was told by a man I respect that he believed women would be offended by the woman in the bikini, especially women in their twenties. I certainly did not intend to offend people of any age and I was glad that a 31-year old woman friend said she was not offended by the woman in the bikini because she thought it was “campy,” and looked like a “period kind of thing.” A woman grad student friend in her twenties said she wasn’t offended because “I think anyone with any cultural literacy would see it as emblematic of the era and the pinup culture.” Another friend in her twenties said “It didn’t cross my mind.” A woman friend in her forties said she was offended, and I suspect a woman I know in her 50s was too.

At a dinner with eight of my Class of ’50 Shortridge friends (three men, six women), I showed them the flyer and explained that some people found it offensive, but nobody got what the problem was (we are the dinosaur vote.) I don’t intend to do more “polling.”

I am especially grieved if I have brought any offense to The Propylaeum, a time-honored Indianapolis institution where I attended Mrs. Gates’ Dancing Class when I was twelve years old. We had to wear white gloves. Many distinguished people attended those classes, including Senator Lugar, and in an earlier era, Janet Flanner, who for fifty years wrote “Letter from Paris” in The New Yorker magazine and won both The National Book Award and the Legion d’Honneur of France.

In a sense, all this seems like “déjà vu” all over again. Although I was an Eagle Scout in Troop #90, a Minisino at Camp Chank-tun-ungi, and a Sagamore of The Wabash, I realize now, at age eighty-six, I will never win The Legion d’Honneur of Indianapolis. I should have known.

– Dan Wakefield